The Preaching of the Multitudes

Why does everyone sound like an evangelical these days?

The elementary school in my neighborhood has a sign outside the main entrance where they once posted messages like, “Welcome back, students!” or “Have a great summer!” Over the last few years, though, those friendly messages have been replaced with subtly aggressive bromides, like today’s, “Peace. Love. Unite. Respect. Forgive. Accept. Teach. Inspire. Joy. Smile.” Aside from the nonparallel mix of nouns and verbs (which drives me nuts), the sign reads like the table of contents from a self-help book. Embrace these concepts and you, too, will be whole.

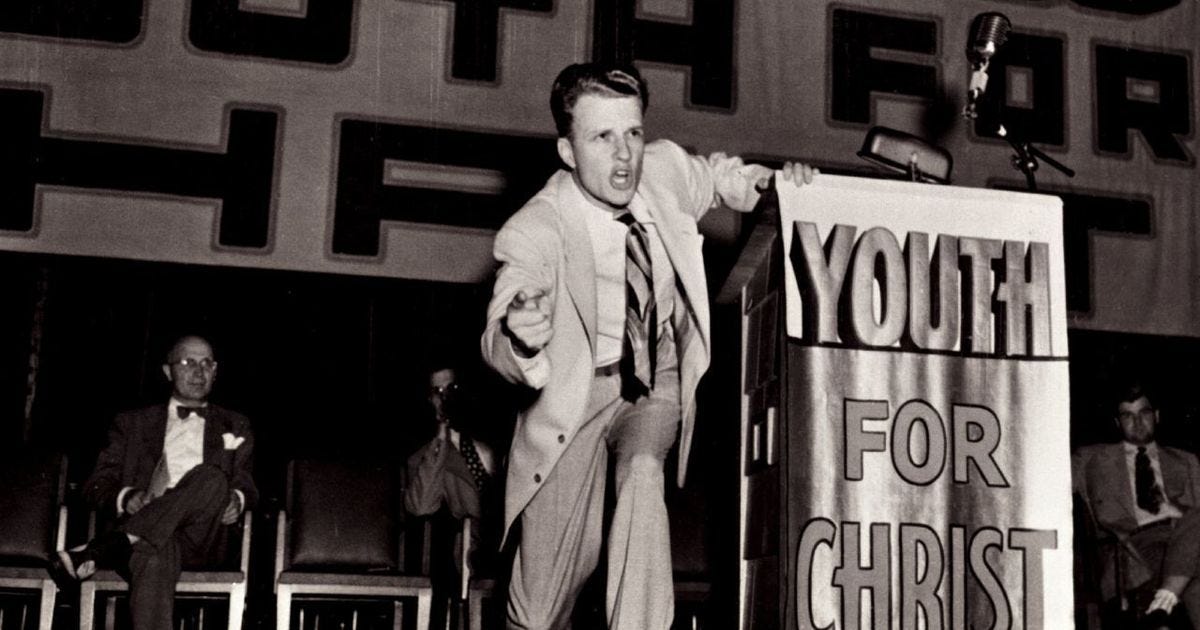

It seems everyone is spouting moral-sounding platitudes these days, as if we’ve become preachers from an ill-defined and irritatingly trite religion. John McWhorter has written extensively about the rise of what he calls Electicism, a latter-day, secular religion that has risen from the ruins of civic and religious institutions. But, since he first identified the phenomenon among fringe groups, I’ve noted a similar posture assumed, and language used, by mainstream, average folks.

You might argue that we talk about the virtues cited above precisely because we crave them, and miss them, in our lives—as if by summoning an idea we can reintegrate it into society. I’d buy that argument if I saw any meaningful trend toward, for example, civility among those who most volubly invoke its decline. Lest you assume I’m dog whistling about woke progressives, I’m not—entirely. Folks in the middle (like me) and on the right do their own preaching, just about different virtues, like faith, virility, patriotism, and even moderation. “Make America Great Again” has become almost holy writ among Trump loyalists, signaling as it does that our president knows both how to return America to greatness and what greatness looks like.

The thing is, when we wave our flags, post our signs, and flaunt our bumperstickers, we imply that we’ve mastered the virtues we reference and are impatiently waiting for everyone else to get on board. It all feels so one-directional. So self-satisifed and preachy.

I grew up a preacher’s kid, so I’m familiar with sermons and prayers and old-school religion. When my father led his congregation in prayer, he generally spoke in the first-person plural: “God, grant us the strength…” or “Lord, forgive us our sins…” I can’t recall him ever using accusative verbs as cudgels the way we do today. He included himself among the sinners he addressed, acknowledging his failings and asking for God’s forgiveness. He spoke this way in public and at home with his family. When he preached, he referred to ancient wisdom, and to theologians who studied that wisdom, to impart a message. Even in his pulpit, before hundreds of congregants, he didn’t hold forth as an example to be followed; he spoke humbly, asking a higher power to guide us all in our actions.

Let’ face it, no one appreciates being preached at. Most people, I believe, are genuinely humble and reasonable and, when acquainted with their failings, generally acknowledge them. When bombarded by coded claims of someone else’s moral superiority, however, those same folks are likely to dig in and fight back. The real enemy is not each other, but certainty—certainty about the rectitude of our own beliefs, and certainty that the other side is irredeemably benighted (and potentially dangerous). We’re all deep into a 21st-century religious war—and not just between the far left and far right. Where once armies battled over interpretations of holy texts, we now arm ourselves with played-out ideological shibboleths. Peace, love, inclusion, and kindness on the left. God, guns, manhood, and country on the right. Without the moderating influence of shared cultural institutions, we’re left to adjudicate everything for ourselves—often on social media or at the end of a bullhorn.

I don’t have an easy answer for this mess except, perhaps, to recommend my father’s use of the first-person plural. There’s something disarming about “us” and “we,” particularly in the context of exchanging views. We are all imperfect. We could be more open to considering opposing views. We can move past this. Doing so, of course, requires believing an American collective still exists, or could, and that we haven’t so atomized as a culture that there’s no coming back. I don’t personally believe we’re beyond saving, but, hey, I’m just a preacher’s kid.

We're living in a new era of Fundamentalism in which secular ideology has replaced religious ideology and Fundamentalists exist at both ends of the secular ideological spectrum. Evangelism goes hand in glove with Fundamentalism.

We need to return to Liberal Pluralism, which provided the foundation for our now waning liberal democratic republic.

Well said, preacher's kid! I think a point to add here is that we're not given to deep, deliberate thinking much these days--so we like bumper-sticker, slogan-based quick "thinking." Relatedly, of course, we're not especially careful users of language these days either. A dangerous mix.